The Availability Heuristic

Analysing its causes, effects, and prevalence in daily life (and football) while gaining a deeper of economics and psychology.

1. Definitions and Context

1.1 Behavioural Economics

1.2 Heuristic

1.3 The Availability Heuristic

2. How Heuristics Work

3. The Effects and Examples of the Availability Heuristic

4. The Availability Heuristic in Football and FPL

4.1 Football & FPL

5. Conclusion

[1. Definitions and Context]

To improve the legibility of the following definitions, I will split them up into subcategories since they can often become theoretical.

[1.1 Behavioural Economics]

Behavioral Economics is the study of psychology and its relation to the economic decision-making processes of individuals and institutions. It is often said to be intrinsically linked to normative economics, which involves ideologically prescriptive judgments rather than factual observations. Essentially, behavioral economics seeks to understand why and how people act in the real world, without relying solely on direct statistical evidence (as in positive economics).

Where Neoclassical economics posits that people have well-defined preferences and make self-interested and well-informed decisions based on these pre-existing preferences, behavioural economics analyses the mistakes we make during this decision-making process and aims to find ways to correct and avoid these errors.

Classical economists believe that people are rational beings, while behavioral economics assumes the opposite. Therefore, behavioral economics must address inconsistencies between desires and outcomes, which is highly relevant to Fantasy Premier League (FPL) and will be referenced later.

[1.2 Heuristic]

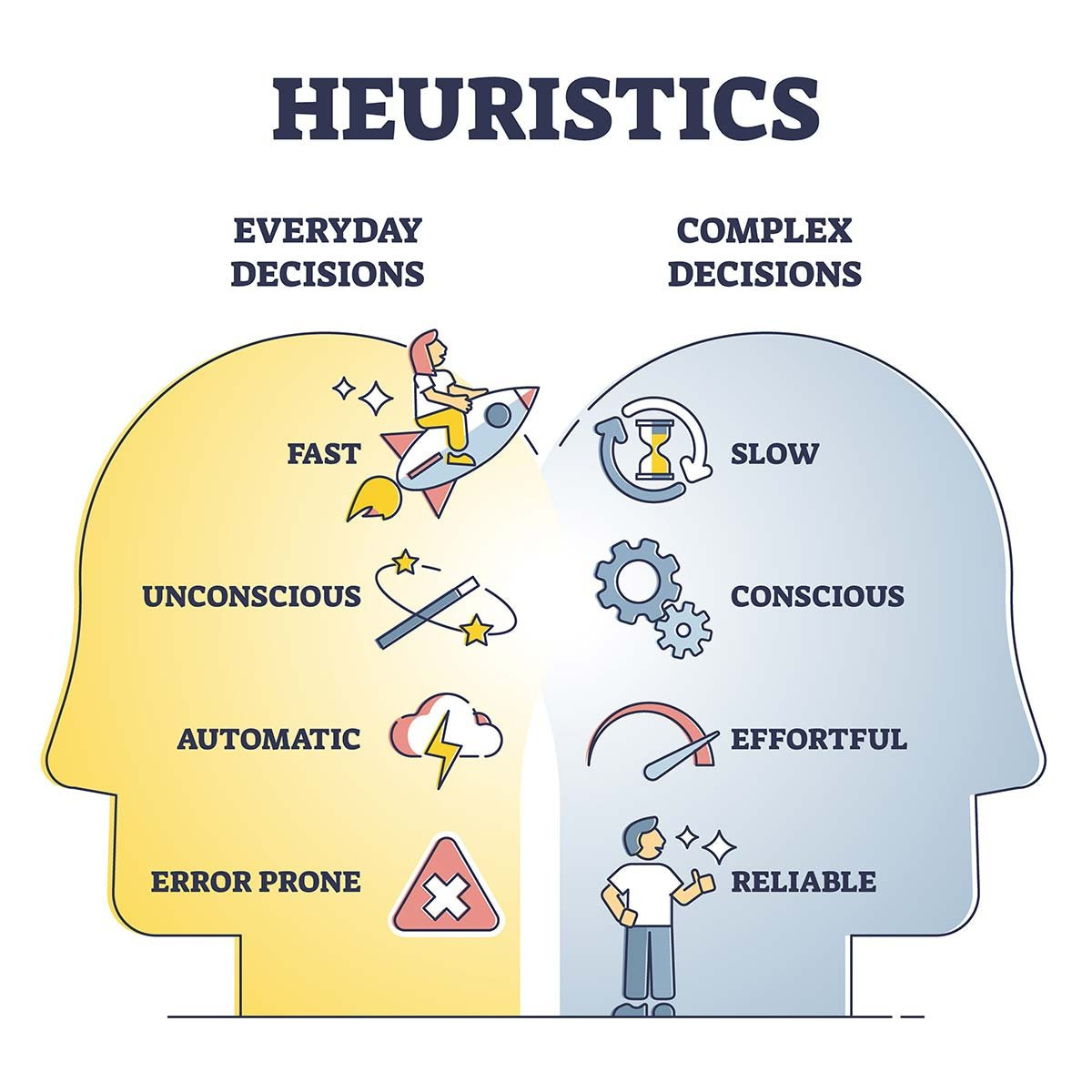

In the context of psychology, a heuristic is a mental shortcut that allows people to make judgments quickly and efficiently. This means we don't have to pause and deliberate on our next action; instead, we instinctively act based on mental cues. While heuristics can make us more efficient, there is a common belief that these mental shortcuts hinder our ability to make rational decisions because we do not carefully weigh the costs and benefits of every possible scenario. However, in practical terms, it is often not feasible to consider every possible scenario, so other factors such as intelligence and the accuracy of our perceptions also influence the decision-making process.

Simply put, heuristics stem from a need to reduce cognitive load, simplify choices and enable us to act quickly.

[1.3 The Availability Heuristic]

Building on the previously mentioned definition of a heuristic, the Availability Heuristic is a cognitive bias* where decisions are influenced by information readily recalled. Consequently, this information is mistakenly perceived as representative of more frequent or probable events. Essentially, when making a decision, individuals tend to prioritize certain pieces of information, often ones encountered recently, and overestimate the likelihood of their recurrence.

*a cognitive bias is the tendency to act in an irrational way due to limited ability to objectively process information.

[2. How Heuristics Work]

Our brain is highly adaptive and inherently eager to learn. Consequently, heuristics can only develop over time. As we make decisions and observe outcomes, our brains create narratives or frameworks that enable us to handle similar situations in the future. It's akin to anticipating a pattern and being able to solve it because we've encountered it before. Therefore, heuristics develop as a result of evolution and basic brain maturity.

However, when we recall past events, especially their outcomes, we often encounter preconceived notions. The existing framework of that experience quickly relates to the previous one, forming a new perspective on the current (similar) experience. This process provides an 'answer' to the problem or a solution without the need for unnecessary mental exertion. This phenomenon highlights a central issue that Behavioral Economics considers: the disparities between desires and outcomes. It's important to recognize that no two scenarios are exactly alike. Consequently, when attempting to solve a new problem, we are subconsciously influenced by new biases. Thus, while we may desire the same outcome as in a previous situation, we often fail to achieve it, resulting in further inconsistencies between desire and outcome due to a lack of rational thought or the influence of other heuristics, such as anchoring.

Some common examples of heuristics include:

When you're stuck in traffic (so you decide to take a different route without knowing the way) [affect heuristic].

Consumers often buy the same brand over and over again, even if the brand isn't what they necessarily need [familiarity heuristic].

Basing opinions on someone due to what someone else said about them [representativeness heuristic].

Guessing that someone who is creative or dressed colorfully is a humanities major [representativeness heuristic].

[3. The Effects and Examples of the Availability Heuristic]

As we know, the availability heuristic describes how certain information can carry greater weight in our thought processes, often leading to incorrect conclusions (though heuristics are still generally effective).

A common example of how we prioritize certain information is the perception of plane crashes. Many people believe that the likelihood of dying in a plane crash is much higher than in a car accident. However, the opposite is true. This can be substantiated by statistics; the probability of dying in a car accident was 1 in 107 (as of 2019), whereas there weren't enough plane crashes to draw a meaningful conclusion. In similar statistics, a person would have to take 3,678,470 flights in their lifetime to be involved in a fatal air accident. (For additional information that has not been included in this piece, click here.) This misconception can be attributed to the fact that whenever a plane crash occurs, its gravity is exemplified and vividly presented by the media. Consequently, we place greater emphasis on it than on a car accident. Perhaps it has been so normalised that it doesn't evoke the same emotional response, or maybe we perceive driving as an unavoidable scenario, hence not assigning the same weight to it.

The quote below, by Daniel Kahneman, embodies the above phenomena succinctly. He discusses heuristics further in his book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow.”

The brains of humans contain a mechanism that is designed to give priority to bad news. - Daniel Kahneman

Even the lottery. Many of us label it as a scam, but have we considered just how deep the rabbit hole goes? The probability of winning the Powerball Jackpot of $1.58 billion was 1 in 300 million (Victor, 2016). However, the image of success, and the people who have achieved it, firmly embeds itself in our minds, causing us to subconsciously overestimate our chances of winning the lottery.

We are prone to overestimate how much we understand about the world and to underestimate the role of chance in events. - Daniel Kahneman

Our susceptibility to the availability heuristic can be intrinsically linked to our sense of self too. For an explanation, I will briefly summarise a study done in 1991.

[Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 195–202.]

Essentially, the ease with which people can recall information has implications for what they actually recall. In this study, subjects were divided into two groups. One group had to list 6 examples of assertive behavior, and the second group had to list 12. After completing this task, they had to rate how assertive they perceived themselves to be based on their answers. Both groups finished listing their examples; however, those who had to list only six examples rated themselves as significantly more assertive. This was because listing six examples was perceived as an easier task in relative terms, leading the participants to correlate their answers with more assertive behavior. The opposite applied to the group listing 12 examples, which was perceived as a relatively tougher task, resulting in them rating themselves as less assertive. This study demonstrates that, intrinsically, availability heuristics and biases operate based on the ease of recall rather than the content itself. After all, this is what the participants used to rate themselves.

“A general “law of least effort” applies to cognitive as well as physical

exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the

same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course

of action. In the economy of action, effort is a cost, and the acquisition of

skill is driven by the balance of benefits and costs. Laziness is built deep into our nature.” - Daniel Kahneman

[4. Football]

I will merge the football and FPL sections because I believe that a deeper understanding of football, combined with comprehensive knowledge of FPL's rules, is key to success in this field. Additionally, most of the information in the FPL section will have a direct impact on football, and vice versa.

[4.1 Football]

For this sub-section, we will focus on outcome availability bias because, from my personal experience, I have seen it occur far more often than I would've liked. Do you recall when I mentioned desired outcomes vs. results in section 1.1? Well, this plays a pivotal role here.

In layman's terms, outcome availability bias is the use of availability heuristics to judge the outcome of an event.

The example below is presented solely for illustrative purposes. Its concept holds greater significance than the example itself, as it can be applied in various contexts. Ironically, by listing this example, I am acknowledging my own susceptibility to the availability heuristic.

The above image was taken from Chelsea’s 3-0 win over Luton Town, in which Raheem Sterling scored twice and was nearly awarded an assist. His npxG+xAG was 1.07, indicating that it was also statistically a good performance. But this isn’t where Raheem Sterling's plaudits caught the attention of viewers everywhere. That happened against West Ham. Even in a loss, Sterling was the liveliest player on the pitch, successfully completing 6 (!) out of his 7 attempted dribbles.

Nonetheless, the goals came against Luton. That match occurred on the 26th of August 2023. And much to people's dismay, when the England squad was announced on the 31st of August, Raheem Sterling was not included. I'll be honest; I think Sterling has received far more hate than he deserved. That said, the uproar on social media when he wasn't called up seemed... illogical? I cannot imagine the same reaction had he not scored against Luton. Perhaps the reaction was from Chelsea fans looking for any semblance of hope or from the voice of the FPL community following his 19-pointer. Either way, the noise died down soon. Why? Eberechi Eze got 2 assists against Plymouth on the 30th of August and scored against Wolves on the 3rd of September.

Suddenly, social media was applauding his inclusion, rather than focusing on Sterling’s exclusion. To make matters worse, Sterling wasn’t called up even after Grealish pulled out of the squad.

"To bring Raheem back in we have to leave someone else out and on the back of our three games [earlier this year] I didn’t think anybody in this group of attacking players warrants being left out," explained the 53-year-old. “It’s a difficult call and Raheem is not particularly happy about it, but I understand that because he’s an important player for us. I’m convinced he’s going to have an excellent season with Chelsea, there’s no doubt about that." - Gareth Southgate

See what I’m getting at here? Sterling’s recent performances were given much greater importance than logic should dictate. We know that Sterling is more than a capable player; we saw it at Manchester City (339 appearances, 131 goals, 95 assists). Perhaps this nostalgia, combined with the importance given to those goals, influenced our thought processes.

But this is a one-off occurrence. No harm done, right? Well, not exactly. I recently came upon this article by Nalin Rajput, and it talks about the special case of Eder. Remember that goal he scored against France in the final of the 2016 Euros? Well, that goal has weighed heavily on our minds. Before the Euros, he played for Swansea and hadn't scored in 15 appearances. But after the goal, he was bought by Lille, where he scored 26 times in 102 appearances. Not ideal for a potential world-beater, is it?

Okay, fans and scouts/analysts fall for the availability heuristic. But surely, managers don't, right? Take a gander at what Sir Alex Ferguson said on the matter:

They weren’t bad buys, but sometimes players get themselves motivated and prepared for World Cups and European Championships and after that there can be a levelling off.

Think of Caicedo leaving Brighton. People initially thought that Brighton would not be able to cope with the loss (although worrying about the lack of a ball-winner/capabilities in transition was justified). Brighton has still managed to do well, though. It's the same with Spurs and Kane leaving, and eventually, it will be the same with Liverpool and Salah. We fall victim to placing a greater emphasis on what a team loses when their 'best' player isn't present. Essentially, we are susceptible to the opposite of the Ewing effect. Even this is an example of placing greater emphasis on a particular notion.

Now, if this can happen to the best of the best, what chance do we FPL players have? To make matters worse, due to the nature of the game, we are very outcome-oriented, even though the outcome isn't in our hands. Ultimately, we can only make 'optimal' decisions to put ourselves in the best position to become lucky. But this is easier said than done. We constantly fall into a cycle of being susceptible to heuristics, hence falling victim to them.

Consider statistics, for example. We may focus on certain data simply because it's more easily accessible than others, and when in tandem with confirmation bias, we have an issue on our hands. It's very easy to spin a narrative to suit the limited data you have to actually support it. Furthermore, data naturally resonates trust. After all, math is objective; it can't have a bias. But when data is presented in a way to suit what the author wants it to suit, it isn't data anymore; it's a story with numbers in it.

For example, if per 90 data is easily available to you, and you're hell-bent on using it, you may apply it to a person who doesn't start often, but rather is expected to make an impact off the bench. Consider Neil Maupay. He's started once and came off the bench in the other, accumulating a total of 112 minutes. However, with this small sample size, he has the 4th highest xG/90 out of any player in the Premier League (1.16). This would be something that's easy to recall, whereas the circumstances around this number aren't as easy to remember, meaning they are forgotten, hence severely lack context.

Media coverage can also influence our FPL/football views. If everyone on Twitter (or X if you're feeling edgy) speaks very positively about a certain player as an FPL asset, we will naturally gravitate toward picking them. Tarkowski's performance in Everton's DGW in 22-23 comes to mind. He had scored a header a few GWs ago, and now his double-header included Villa and Arsenal. He's a perfectly good pick in isolation, but no one expected a clean sheet. Essentially, everyone was relying on a header. His npxG+xAG (over the season) was decent, I suppose, at 0.16/90. However, goals from set-pieces are far more random and unpredictable, especially when you weigh them against clean sheets. For most people, it was far easier to simply listen to content creators (as they provide genuinely good advice) than to check the data for themselves.

[5. Conclusion]

To conclude, simply being aware of these heuristics and biases can go a long way in life. By knowing them, you reduce the chance that your subconscious picks up on them, giving you a greater grasp of reality as you know it. Think about it. Now, you won't spend those $5 on a lottery ticket, and you won't get in a fight with the next Albert Einstein because of the color of his clothes. You can also learn the difference between outcomes and systems and learn to separate what you can and cannot control. You can exert that much more control over your life and make it your own. Take some time off, look at things from a neutral's point of view. It helps more than you think.

“Nothing in life is as important as you think it is when you are thinking about it.” - Daniel Kahneman