👉 Definitions

Okay, let’s first get a few foundational thoughts out of the way:

Not all injuries are the same. Some can’t be prevented, while others can.

“Preventable” injuries are things like muscular injuries which can happen because of overtraining (often during training) or undertraining (not enough fitness work on a general basis).

Unavoidable injuries are contact injuries.

Suffering an unavoidable injury doesn’t make a player injury-prone.

Take Wesley Fofana, for example. His broken fibula in 21/22 was because Fer Niño decided that was the day he just had to try his hand at martial arts, and there was nothing Fofana could’ve done to stop it. Sure, it might affect his injury susceptibility going forward, but in that particular case, Fofana simply couldn't have prevented it.

But on the other hand, what about his recent hamstring tear? Was that preventable? Who’s to blame? Fofana? Maresca? Well, it’s one of them.

And this is exactly the situation Brighton and Hove Albion Football Club find themselves in. So, let’s take a look at Lewis Dunk’s calf. And pray for Jan Paul van Hecke’s hamstrings.

👉 The Injuries

So, that’s one complicated graphic. Essentially, it tracks (almost) every injury suffered by a Brighton player this season. Hooray.

The first thing to note is that Fabian Hürzeler has been quite vague about injuries, making some of them difficult to quantify. That said, the ones I have been able to discern are appropriately labelled as “muscular” for muscular (avoidable) injuries.

And there have been a LOT of muscular injuries.

I mean, just look at the defenders—six out of eight have suffered muscular issues (two hamstring, one thigh, two calf, one unknown)—which is… terrifying.

But before diving into the causes and solutions, it’s important to first look at how Hürzeler manages injuries.

👉 Rest, Recovery, Precautions, Recovery, Sprinting, and Did I Say Recovery?

Hürzeler is very careful with players returning from injury.

When reintegrating them, he’s more than happy to give them a couple of sub appearances off the bench before thrusting them into his demanding (to say the least) pressing scheme. Jan Paul van Hecke came off the bench in GW8 (Newcastle), Lewis Dunk in GW22, João Pedro against Bournemouth—the list goes on.

So, point one to Hürzeler for managing workloads. He always says his first priority is his players and managing them on an individual level—and he means it. Player wellbeing comes first.

The next thing I’d like to mention is that Hürzeler demands that his players run. And run A LOT. You work hard as an individual, and that’s what makes the collective tick. You go out there, win your duels, press to disrupt, win that second ball, run some more, run a little bit more, pause to take a breath, and run a little more.

So it’s pretty intense. In fact, Brighton are 16th in the league for opponent build-up % allowed, so the press is clearly working.

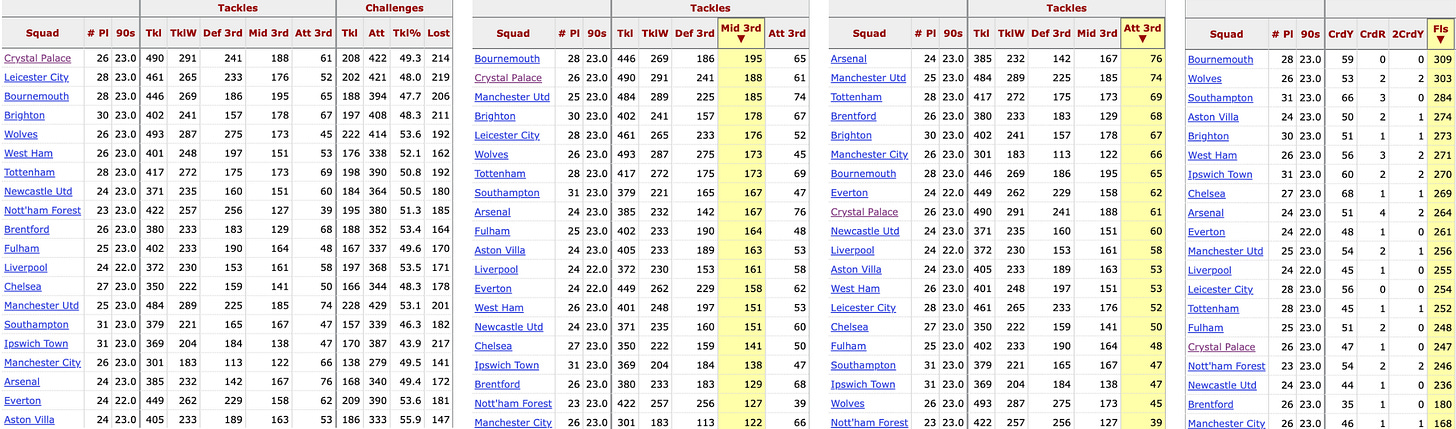

Anyway, finding pressing data is a little difficult, but here’s some defensive action data that should do the trick (let’s not question why Palace is the only purple-d link):

But this one stat… yeah, this one stat, it bothers me. And (at the time of writing), it’s Brighton’s high defensive line.

👉 The Dog Days of a Defensive Line

Run fast your mother, fast for your fatherrrrr, run for your children, for your sisters and your brothers 🎵

…and why not also run because of where you’re playing on the pitch?

Brighton’s defensive line has an average height of 48.05 metres, making it the third highest in the Premier League.

Now, in isolation, this is fine. Great, in fact. You press high, restrict the space your opponent has, win the ball back closer to the opponent’s goal, increase the distance to your own goal, be a complete nuisance near the opponent’s box with a higher volume of runs/a smaller distance that needs to be run, and yeah, score a few goals.

But in Brighton’s case, things are a little more complicated.

The DM roams a lot OOP. In fact, they’re almost used as a m2m presser. Factor in the fact that the other two midfielders run high and roam in possession, and you *largely* lack a midfield.

So, the CBs step in.

Sure, the fullbacks do in the first phase of build-up, but by the time Brighton turn the ball over, they’re too wide to prevent central transitions.

So stopping this oncoming transition is all on the CBs. A lone soldier against an army. A lone soldier with a tight hamstring.

Now, they have all the distance of the high line behind them. Do they run back and defend closer to goal? Do they jump their defensive line further and try to counter-press?

Should I stay, or should I go? (doo doo doo doo)

They stay. Lewis Dunk lunges forward, tries to win the ball, and misses. Jan Paul van Hecke watches on in horror. Joel Veltman gasps. Pervis Estupiñán shakes his head. Carlos Baleba nods. And, in cohesion, they start to run.

Run, run, run. You have to try all that distance against players faster than you, after all. Over and over again.

And, well, this takes a toll on the body. A toll that you pay off in the form of muscular injuries.

👉 Flex That Pulled Hamstring

Now, in a roundabout way, this brings me back to Brighton’s defensive line and the premise of a footballing philosophy—so I have to ask:

Where do you draw the line? When does maintaining a philosophy turn into a rigid system—one that becomes my way or the highway?

Because, if you ask me, consistently running a high line with your main CB options being:

Lewis Dunk (at 33 years of age)

Adam Webster

Julio Igor

…and that’s it—

is simply asking for trouble. None of the three are particularly quick, and the first and last aren’t exactly the most sprightly (Dunk’s recent calf issues and frequent hamstring tightness are evidence enough of that).

Now factor in the fact that Mats Wieffer (Brighton’s second-most important ball-winner) has missed half the season through injury, and, well… who or what is there to stop transitions—let alone prevent them from having to run mile upon mile?

And if your defensive line is unsustainable (and it sometimes can be in Brighton’s case), you’re sort of setting your defenders up for failure—simply because they cannot handle what they’re expected to do, and that’s through no fault of their own.

Essentially, just line up with pacy wingers and a big, strong CF, and you can beat Brighton 7-0. Hopefully, that never happens.

👉 Solve the Solvable

Now, look. Over/undertraining (including matchday demands) leading to muscular injuries are just a small part of the harsh and unforgiving world of sporting injuries.

But it’s important not to get drowned out by all the noise and to recognise the cause of every injury—because not every injury is the same. They can be similar, but they’re triggered by different causes and provoke different reactions.

You can’t do much about a crushed toe if an elephant steps on one of your players, but you can recognise when you’re demanding too much of them.

And since it’s a players’ game, well… maybe some compromise is a good thing. In Brighton’s case, that might mean younger, more athletic CBs with longer strides—someone like Leny Yoro, funnily enough. Or just stepping away from the high line when you don’t have players to sustain it (look at who you have in transition, anyway).