👉 Progress at Brighton

Since Potter spent a sizeable chunk of his career at Brighton, let’s use his time there as a basis of comparison.

Specifically, we’re comparing Brighton’s progress across 2020/21, 2021/22, and 2022/23.

2020/21 was Potter’s second season at Brighton, 2021/22 his third, and 2022/23 was De Zerbi’s first (and the first post-Potter, barring the first six games). So, there’s some inference value in the translatable effect.

👉 2020/21

I’m just going to need a moment to process the fact that Brighton were 3rd for xGA in THE LEAGUE.

3rd for xGA, 5th for xGD, 11th for xG. Based on these shallow(er) stats, Potter coached a darn good season for a team that finished 16th.

But I suppose the first signs of a typical Potter side are already evident here:

Strong possessional signs considering the situation Brighton found themselves in.

A low number of counterattacks because a build-up can never be quick (!!).

Essentially non-existent box efficiency (who needs goals anyway?).

An intricate (specific) press rather than a cohesive team-level one.

👉 2021/22

9th. Talk about progress, hey? 6th for xGA, 7th for xGD, 10th for xG. Roughly the same in terms of expected data—just with a bit more positive variance and a slightly better, more cohesive squad.

An improvement in duels is always a good sign, and Potter got some good players to work with:

👉 2022/23

6th. 0.158 of Graham Potter and 0.842 of Roberto De Zerbi—you’ve worked wonders.

2nd for xG, 6th for xGD, and 7th for xGA. Whew. A squad capable of beating anyone, and 31,477 people with hopes and dreams clinging on to every good memory.

👉 Past Progress as an Indicator of Future Success

When assessing how Potter leaves a squad, Brighton isn’t necessarily the best case study. Managers are hired within a certain philosophy, expected to fit a broader vision, and to work with both existing and future signings.

It’s essentially an endless cycle—managers are just cogs in the wheel.

So, did Potter leave Brighton stuck in a rut, only capable of one style of play?

No. He improved them across all possession-based metrics, increased ball progression quality and quantity, raised their defensive actions, reduced PPDA while strengthening their defense, and ultimately turned them into a solid, run-of-the-mill, reliable side.

And here’s a graphic showing Brighton’s pass maps—all against Leicester (of varying strengths) under Potter, De Zerbi, and Hürzeler.

Death, taxes, footballing philosophies, and conceding twice. To Leicester.

👉 Media and Player Management

Media work isn’t Potter’s strongest suit.

A lot of this sentiment stems from his time at Chelsea, but we should really exclude that whole period. Forget it ever happened. Like a bad memory. Obliviate (ahaha, cliché Harry Potter joke), one might say.

He was thrown into a very messy situation, and although he didn’t necessarily help his own cause, he was made the scapegoat. Sure, he had his deficiencies, but some of the headlines that came out during periods of struggle seemed like pure clickbait. After all, why not pile on someone already under pressure?

Also, for the dressing room to get crowded enough for players to literally not have a place to sit… no, there’s just nothing you can do as a manager there (except blame the board, because they deserve to be blamed).

But even in THAT position, Graham Potter had this going for him:

Ben Chilwell: “I've been in dressing rooms before where you know in your head that there's a bit of a divide between staff and players... and for sure, this isn't one of them…

“Potter has dealt with it all brilliantly the past few months.”

He was clearly well liked, but was he respected?

I mean, you have to assume there was some degree of respect, and the media blew the rest out of proportion, because, at least to me, it isn’t conceivable that players would blatantly disrespect their boss, even if he reportedly lacked charisma.

👉 Pragmatism

This, to me, is just a very intriguing aspect of Potter’s management. It reminds me a bit of Tuchel, really, considering I believe him to be the crème de la crème of individual game tweaks.

Firstly, I think pragmatism is great. It’s good to surprise the opponent, and specific match tweaks will do just that—you’re playing to your strengths while specifically countering the opponents’ strengths.

But this is exactly where my doubts come from—if you’re switching it up (and to no small degree) every game, how do you build upon your strengths?

Potter does have a basic foundation (largely possession-based) to build on, I suppose, but at some point, constant chopping and changing is likely to cause some instability. But does this instability warrant a tactical advantage?

Let’s get a second opinion on this. Fabian Hürzeler was forced to switch to a back three against Southampton, what with Brighton’s hobby of collecting injuries as if they were precious gems, and he was asked about it before Brighton’s next match:

Anyway, let’s further analyse pragmatism conceptually in the short term while assuming football to be a players' game (because it is). There is merit to analysing how it could affect West Ham in the long run, but that becomes so presumptuous that its inference value proportionately deteriorates.

👉 Short Term

Match-specific tweaks, and even having a plan A and B for said match, open you up to huge bouts of variance. If the opposing manager lines up how you’d expect them to, hooray! You know exactly how to stop them.

But if not, and you’ve spent hours and hours training for one particular scenario as opposed to also developing the foundations (this is a bit of an extreme example), you’re in big trouble.

Now, if you have the absolute best players in your team, that’s great. Variance naturally reduces because player quality is enough to plough you through. And while I think West Ham have one of the most talented squads in the Premier League, ever since Moyes left (and arguably for a few months leading up to it), they’ve faced instability. Is there room for short-term pragmatism?

And when pragmatism doesn’t work—player quality, variance, whatever—will there be continued persistence in trying again, and again, and again? Can Potter rally confidence within the squad to go again?

👉 Pragmatism—Conclusion

Look, if all is handled well behind closed doors, pragmatism is great. Potter just has a lot of question marks around whether he can actually manage the behind-the-scenes stuff.

I have faith, and there’s reason for West Ham fans to as well. But where pragmatism links to the foundations of one’s footballing beliefs, you have one of Potter’s biggest criticisms.

👉 Just Score. Please.

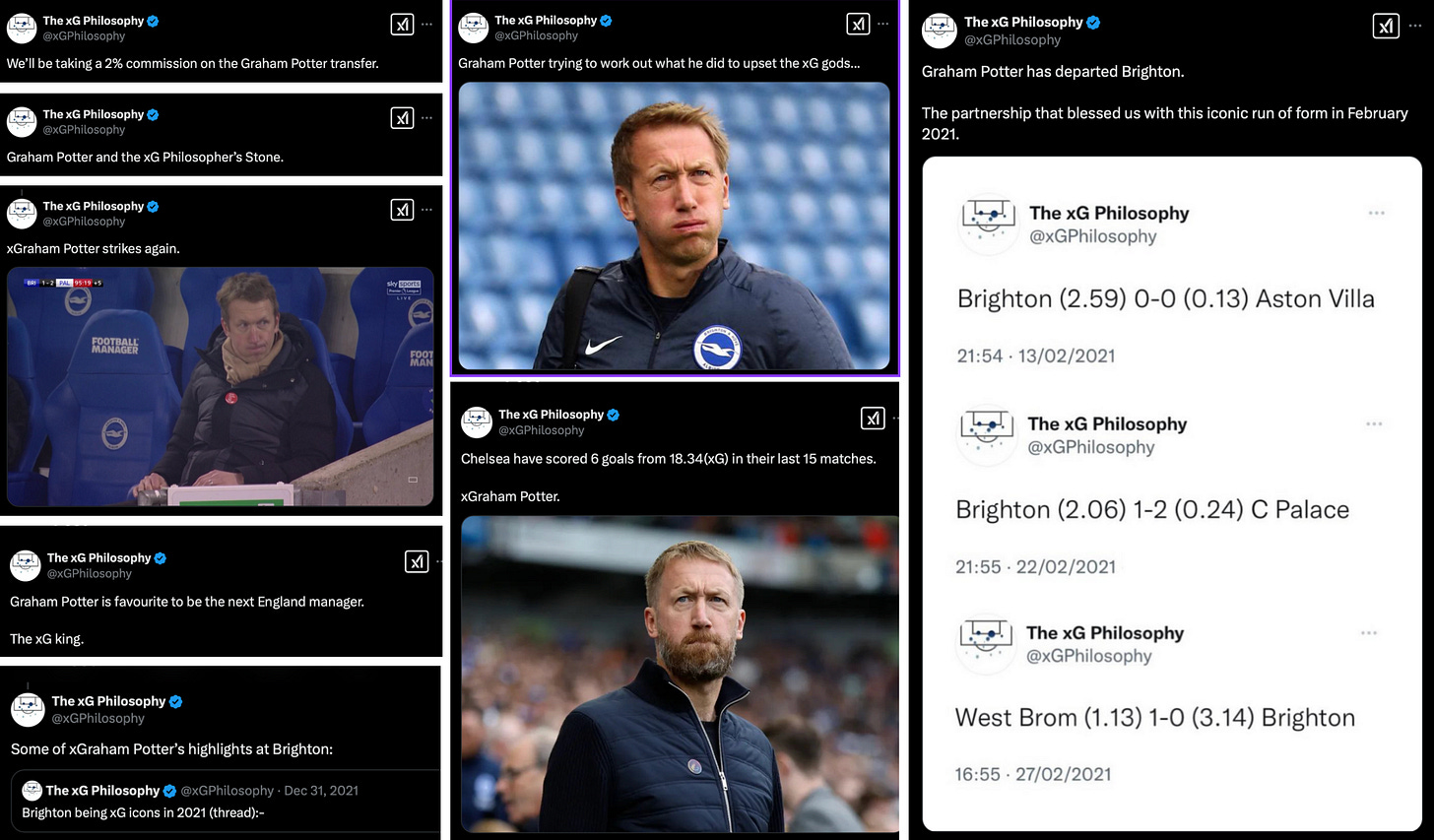

Graham Potter and underperforming xG. The couple Romeo and Juliet hoped they could be.

The core of the issue comes down to not creating enough—and not doing so consistently. 14th for xG in his first season, 11th in the next, Neil Maupay at the helm—you can see where this is going.

Here’s a graphic showing all of Brighton’s shot locations from the 2020–21 season:

And the output just isn’t… great? So many shots, most of which aren’t of high quality either. You could certainly argue that Potter’s side builds up so slowly that it almost becomes predictable to opponents when they shoot—because they know where and when each player will be—and they don’t have the absolute quality to overwhelm the opposition.

Look, we have to acknowledge that some of this is on the players. If players miss chances—and do so over and over again, especially when they’re missing good chances—well, as a coach, all you can do is bury your face in the warm, comforting depths of your palm, console your players, and give them the confidence to try again.

But at the same time, it’s important to look at the type of chances your players are getting. If you have a very one-footed striker biased towards his right, and every single one of your chances goes through his left, you’re just playing through a very counterproductive system.

In the 2020/21 season, Neal Maupay (above) took a lot of shots from outside the box, and such is the nature of his incomplete ball-striking that they just weren’t very powerful. Could a slight nuance in tactics—via wide runners allowing Brighton to stretch the pitch and gain a numerical advantage in the box—enable Maupay to push forward and shoot from five yards in front of goal?

Perhaps.

Would that have led to more goals?

Yes.

Meanwhile, Potter’s Chelsea had an xG/Shot of 0.1. Yikes.

I suppose Chelsea spent so much of the season in losing positions that there was just an obvious desperation to score, which lowers the quality of shots you take. You also end up taking these shots against teams that sit back, given that they’re defending a lead, so you really have nothing going for you.

Furthemore, as per The Athletic, Potter’s Chelsea scored 28 non-penalty goals from 395 shots, with a conversion rate of 7% and an average distance from goal of 16.2 yards. The league average conversion rate was 11%.

So Potter has to find a balance between trying to control everything and simply relinquishing some of it—accepting chaos. West Ham have the quality to thrive off it (your Kudus’ of the world especially), and they’re used to a more direct system anyway. Playing to your players’ strengths by adapting your own strengths.

And then it comes down to Potter’s own ability to gain his players’ trust. Can he instil the confidence in them to shoot after they’ve just missed what should’ve been a goal? Does he give them the room to drive with the ball? Shoot from here? Shoot from there? A hug after they really shouldn’t have shot from there?

👉 Conclusion

I like Graham Potter. It’s hard not to love a manager who can supposedly adapt to anything the opposing manager throws at him because it fits the conventional idea of the idyllic coach.

But at the same time, my faith in Potter to consistently deliver has gradually dropped to the point where I don’t see him in the upper echelon of the next generation of managers.

Will he have a good career? Yes. An excellent one? I have my doubts. Until you give your players a reason to have faith in you, it’s just hard to instill confidence.

So this is an exceptional case of “only time will tell.” But what time currently tells us is that Potter has drawn 62 of 216 games across Swansea (21), Brighton (43), and Chelsea (8). And while some of those draws came in games he might’ve been expected to lose (so, in that sense, a positive), at some point, a few more goals wouldn’t hurt.