I'll start off with a warning: Don't read this if you're worried about growing as a person and expanding your boundaries. If you want to become more self-aware, hello, I'm Adi. Get ready to see a whole new world.

CONTENTS

1. Definitions and Causes

2. Examples

2.1 Everyday Decision Making

2.2 Businesses

2.3 Football

2.4 Fantasy Premier League (FPL)

3. Solutions

4. Conclusion

[1. Definitions and Causes]

(Plan) Continuation bias is the cognitive bias that subconsciously prompts us to continue with our original plan despite changing conditions.

“I’ve thought through my original plan so thoroughly, so of course it has to be right?”

Okay, imagine this: you’re in university, and while being all gung-ho and excited about all these new courses you can take, you choose to major in... history? Gah, what were you thinking?! But no worries; your university is flexible. They’ve seen hundreds of students run into the dean’s office, begging to change their major to... well, literally to anything.

So that’s what you do. But wait. “What if I’m meant to do history? Sure, the only thing I know about history is that my grandfather is old, but I planned it out, so maybe I’m better off doing history."

Where that may be true, you may be falling victim to sunk cost fallacy. Or even social pressure.

So even though you didn’t want to do history, you end up taking it, leaving you miserable for the next four years of your life. Neat, eh?

That’s the issue with continuation bias. There are just so many things that can cause it.

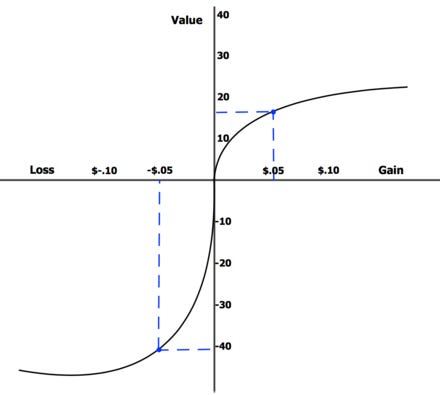

One such cause is loss aversion. Kahneman and Tversky (1992) suggested that losses can, psychologically, be twice as powerful as gains.

Just as any rational man does, they conducted a study on this matter. In some cruel, sadistic way, the study has become far too apt for this morbid, post-COVID world we find ourselves in.

Two groups of participants were asked to imagine that the U.S. was readying itself for an outbreak of a disease that would kill 600 people.

Group one was shown two possible remedies:

If Program A was implemented, 200 people would be saved.

With Program B, there was a 1/3 probability that 600 people would be saved, and a 2/3 chance that everyone would die.

However, the questions were framed differently for Group two.

With Program C, 400 people would die.

With Program D, there is a 1/3 probability that nobody will die, and a 2/3 chance that 600 would die.

“But, Adi, what was the point of telling us this?”

You see, my dear readers, the respondents voted for options that were framed to make them appear as if they were saving lives. All your options naturally saved some lives, but when you read the above, which one feels less death-y, and more “Yay, life!"

72% of participants voted for Program A, and 78% for Program D. This was because they’re loss averse.

“So, loss aversion, sunk-cost fallacy, social pressures, confirmation bias, and overconfidence can cause continuation bias? I may as well curl up into a ball and start hibernating because there’s simply no way I can avoid it.”

See, that’s where you’re wrong. But before we get into the solutions, let’s take a look at some examples. You need to know what you’re looking out for, after all.

[2. Examples]

"Adi, after you’ve given me the biggest existential crisis of my life, you better give me some good examples.”

Okay, okay, let’s talk about some relatable ones, shall we?

[2.1 Everyday Decision Making]

Remember my friend Billy? Yes, that Billy, who was the poster-boy for action bias.

You see, Billy works at a quaint little grocery store. Business is slow, and his manager, Jerry, (imagine the most vile person you can think of and why did you think of your in laws?) is pressurising Billy to grow his business. The Joker to Billy’s Batman.

Hence, Billy starts a buy-one-get-one-free campaign on packets of carrot sticks. But this doesn’t change much for Billy’s store. Demand is still low, and now they make a loss with the sale of each carrot stick.

Surely Billy should change his strategy now, right?

But Billy doesn’t. Billy’s worried. Billy sticks to the plan, fearing that changing it, even for the better, would admit a loss and show weakness. He’s worried that this will make him look even worse in front of Jerry.

So he sticks to the plan, and the store eventually shuts down due to an invasion of rabbits that caught a glimpse of the free carrots.

See what I’m getting at? Maybe another example will help.

Imagine you’re investing in the stock market and see a great investment opportunity. Naturally, you invest in the stock (think of the growth potential!). But then, something changes. The value of the stock falls, and you have to decide whether or not you hold the stock, in hope of the market rebounding.

So, you sit there. You sit there, and thoughts swirl around in your head. “Loss aversion. Sunk-cost fallacy. Overconfidence (my plan is good, trust me!). Society will see this as a sign of weakness. What of the opportunity cost?”

All the above thoughts coerce you into holding this stock. Coerce you into your original plan, even when there’s clearly new evidence to suggest doing otherwise.

The above two examples are exactly what continuation bias is. Succumbing to its many causes, you continue on with your original plan, even though all evidence suggested doing otherwise. The reason you’re not able to adapt and evolve. The reason pilots land their plane in dangerous weather, leading to numerous plane crashes.

[2.2 Businesses]

It’s the same with businesses. Just as we continue holding on to a failing stock, businesses may hold onto failing business strategies.

Think of Blockbuster. Ahh, the nostalgia. The brick-and-mortar, the rental CDs, and a time before all this pesky new technology.

And then came along Netflix. Blockbuster did attempt to adapt, of course, as they saw what Netflix was building toward. However, a majority of their funds went into developing what made Blockbuster - the brick-and-mortar physical stores - Blockbuster.

Continuation and overconfidence bias eventually led to Blockbuster’s demise as they rejected an offer to buy Netflix.

Even Blackberry. At one point, Blackberry held 50% of the U.S. mobile smartphone market. However, their resistance to touchscreen phones, instead deciding to stick with the classic keypad/small screen design, led to Blackberry’s demise.

Hence, people left one fruit for the other, and now are in love with Apple. Steve Jobs really missed a trick by not calling it Blueberry, didn’t he?

So just as we hold on to our stocks hoping for an upturn, businesses hold onto their technologies, their marketing strategies, their business models, as that is what made them successful. They believe that is what will make them successful again.

Of course, you shouldn’t always deviate away from your business’ core philosophy - that’s what makes your business, your business. But you should be open to it, at least.

[2.3 Football]

Just for today, you are Pep Guardiola. Surprise! You've lost all your hair.

You're loving life, playing in a system where both your full-backs get high and wide to hold the width. But you want something more. You want your right-back to invert into the midfield. So, you implement this system. It's now your go-to.

But what's this? Lo and behold, Joao Cancelo's back at Manchester City. So, you force him into that RB position, even when it simply makes no sense.

But you know what would've made sense? Joao Cancelo holding the width down the right. It would've been perfect.

However, you stick to your inverted right-back plan and refuse to deviate. You'd have to cut your losses and admit any Cancelo wrongdoings, after all.

You know that, objectively, using Cancelo to hold the width was the correct decision, but you can't bring yourself to do it. Whether it's pressure from the fans, blind optimism, or sunk-cost fallacy, you stick to your original plan and fall victim to continuation bias.

Seeing that continuation bias in football can also go the other way (instead of buying different players to accommodate a new system, you change the system to avoid deviating from the players you've bought), it can be quite potent.

Especially when you reach the top-flight, where it's a game of small margins. Small margins that explode into epic proportions.

[2.4 Fantasy Premier League]

“I’m Wildcarding in GW 19,” you think, “We’re going to have a double gameweek in gameweek 20 after all!”

And the weeks pass by. Your hair grows raggedy, your kids grow older, learning to take their first steps and walking out of your house as all you do is spend days waiting for a DGW 20 announcement. “I need to Wildcard!”

Another week passes by. You’ve not left your house in five weeks, and your rent is unpaid. Your landlord is forcing you out. “But, my wildcard!”

Time passes by, and it’s evident that there is going to be no DGW 20. But you wildcard in GW 19 anyway because that was your original plan. You bleed incredible amounts of EV and get 19 red arrows in a row.

This is the potency of continuation bias in FPL. Despite all the new information you get, you don’t restructure your original plans.

Why? Overconfidence in your original plan. Fear of FPLMaster123 on Twitter calling you out for “poor decision-making.” Laziness, even. And your results are proportionately worse off than if you’d managed to put loss aversion behind you.

Continuation bias doesn’t necessarily have to be something of the same magnitude as a Wildcard. It can even be something as common as transferring a player out.

Say you plan to sell Bruno Fernandes in GW 10 because his fixtures get ridiculously hard from then on. And between GW 5-10, his fixtures are average. In fact, they’re pretty decent. But his underlyings are poor. He’s been taken off penalties and set-pieces, and now plays as deep as a 6. But you keep him. You hold him, hoping for something that he doesn’t have anymore, living with the ghosts of the past.

And he blanks in all four of those weeks. The data pointed to it, but you refused to accept it.

And that, dear reader, is continuation bias.

[3. Solutions]

Okay, let’s fix the aforementioned existential crisis now, shall we?

Firstly, simply being aware of continuation bias is a step in the right direction. So pat yourself on the back; you're doing a good job!

The next step is to reflect. Reflect upon your decisions while considering any new information, and see if your choices align with what you want your future to look like.

Take advice from other people, but of course, separate your own opinion from theirs before doing so.

Aristotle said:

It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.

So, seek out these perspectives and gain a broader understanding of the predicament you find yourself in. But know where you stand.

That said, knowing where you stand isn’t enough. Embrace change. Embrace the possibility of being wrong, and work on the solution. Frankly, no one cares about your mistake as much as you do, and if you rectify your mistake—if you get to your solution—people will start caring.

Take risks. Yes, opportunity costs and losses of utility will hurt, but you won’t know what you can achieve until you take that risk. $0.05 is ultimately just $0.05; the utility is what you make of it.

Be objective. Of course, let emotions play a part in your decision-making, but being able to rationalize and separate objectivity and subjectivity will make your thought process that much clearer.

[4. Conclusion]

Does this mean that you should always change your plans?

No, not necessarily. Your plans could be right. But they could also be wrong.

Identifying and working on them, even if it means completely restructuring them, can yield proportionately better results.

This distinction is key.

Even if it means changing years of work.